by Juliet Neidish

Kun-Yang Lin’s dance career spans decades and has been recognized by awards and grants both in his homeland, Taiwan, and in the U.S. His choreography has been seen around the world. After joining the dance faculty at Temple University, Kun-Yang Lin made the decision to transfer his company’s base of operations to Philadelphia, facing the challenge of creating a new dance company from the ground up. As it turns out, Mr. Lin has managed to extend his local artistic outreach even beyond the university and his dance company. His CHI Movement Arts Center built from an abandoned warehouse in South Philadelphia is now a thriving multi-purpose studio offering an array of movement classes, studio rental, and performance opportunities, as well as being the training and rehearsal space for his company. Five years is a very short time to develop a strong, cohesive dance company with a significant following. And yet, this is what director Lin has most certainly achieved.

Kun-Yang Lin/Dancers (KYL/D) celebrated its first five years with a retrospective concert presented at the renowned Painted Bride Art Center in Philadelphia. (November 7-9, 2013) In this concert, the company presented six of Mr. Lin’s works dating from 1993- 2001. Four of these were Philadelphia premieres. The one new piece on the program was choreographed by company member Olive Prince.

Each of his achievements — full-time university post in dance, active dance company, and community arts center — is a feat in itself in these times of high rents and scant funding for the arts. In fact, the whole notion of the single choreographer dance company, the model that basically served to build the entire genre of American modern dance, has all but disappeared in recent years. It had been the norm for dancers who wanted to start their own companies to teach dance classes in which they honed and then chose their company members while at the same time building up an audience. Having one’s own studio or loft in which to teach, rehearse and perform, made possible the long hours of training and rehearsal process needed to develop and transmit a personal choreographic style. Recently, as choreographers have found themselves less able to afford their own studios, they turn to renting space by the hour. With rental rates soaring and a dearth of adequate spaces, choreographic process has been undermined. A home for a dance company has become rare, and therefore, so has the institution of the small dance company. At one point, the idea of the “pick-up company” made famous by choreographer David Gordon, was a novelty. But now fewer and fewer choreographers even try to maintain their own company, and must pick their lot of dancers on a per performance basis. Contemporary dance has adapted and good work is still made, rehearsed and performed. Dance alliances and shared performing spaces are beginning to pop up and establish themselves. And as is normal and natural, dance and performance styles are always evolving. However, what does seem like one of the liabilities of making dance today is the challenge for a choreographer to transfer fully his/her own personal style or nuance to all of the performing dancers. Now dancers come to the work as “ready-mades”, or — as Susan Foster once said — paralegals, as opposed to those who historically had the luxury of experiencing ongoing training and molding by the choreographer-director.

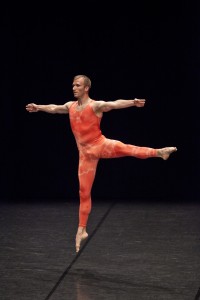

As Lin has been able to build (rather than dismantle) a company with a home base, what connected all of the pieces in his retrospective, were dancers who were highly fluent in his particular movement style. Nine dancers performed in this concert, many of who were quite young, and yet they all presented Lin’s work with a full understanding of his vision. This was very satisfying. Despite differences in age and prior experience, each dancer found a strong personal relationship to the work. And although the work required strong, grounded technique, their technical proficiency alone was not what made this company stand out. It was rather that each dancer in each piece was able to create an invitational entryway into Lin’s poetic dance vision.

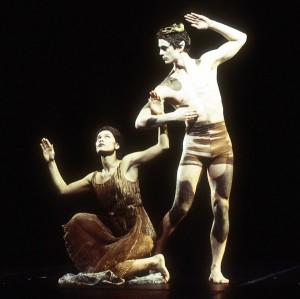

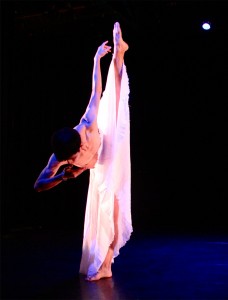

Except for the sprawling group piece, “Shall We…?” (2001), the other choreographies by Lin were solos or duets. Each encapsulated an intriguing snapshot or perhaps, brief poem. While the works were rich and engaging for their abstract movement design, each also hinted at something particular within the realm of human existence. For example, the notion of challenge or fortitude in “Butterfly” (2000), or secret tenderness in “The Song that Can’t be Sung” (1999). The works are portrayed through an interesting use of movement timing. There are brief bolts of fast sequences that lead to quieter swells. It is almost as though the quiet movement directs us to follow a trail or trace of the fast segment as it threads into the slower passage. And yet, despite the speed, the dancers were able to articulate the fast movement with a visible precision that normally is not so clearly present at such a fast pace. I soon discovered that like finding the little gift inside a box of Cracker Jack, each piece contained at least one arresting visual feat in the way of a thoroughly unique balance or lift. When least expected, the “Ah” moment would crystalize and then immediately go away. Aside from only a mere allusion to a story in each piece, another reason for their poetic quality is that they take place without a traditional beginning, middle, or end. Each seems to begin already in progress and then simply fade out. Mr. Lin’s choice to use strong music, i.e. music that we are always aware of, tends to create a soundscape that envelops the dance. Music is not danced to but lived in. The musical background is an integral part of the vision, as is the lighting by Stephen Petrilli — both elements enhance this mysterious choreographic world.

I found Ms. Olive’s piece “to dust” (World Premiere), a strong complement to the program. She possesses a marvelous ability to create unusual patterning of the seven dancers as she placed them across the stage. The stage remained alive throughout as asymmetrical patterns kept refiguring. The aesthetically pleasing brown and grey costumes lent a feeling of autumn leaves infused with conversational attitudes expressed through the body language of the dancers.

The audience at Painted Bride clearly connects deeply with this work. I would be interested in seeing the direction of Mr. Lin’s new work. Since these dancers, new to his older work were so well versed in interpreting it, I can only imagine the synchrony they could have with work made specifically on and for them.