The choreographic retrospective of Yvonne Rainer’s work now underway at the Dia Art Foundation in Beacon, New York (October 22-23, 2011) is an important event for audiences interested in Yvonne Rainer’s dance and the development of the sixties choreographic avant-garde. Two other installments will follow in February and May 2012. Yvonne Rainer, who recently published an autobiography (Feelings are Facts. A life) and more recently still a collection of poems (Poems) is expanding into a figure of immense artistic stature and vitality even while we are given a chance for retrospection. The Dia: Beacon retrospective is an integral part of Rainer’s return to dance from film first announced in 2000 by her production After many a summer dies the swan: Hybrid for the White Oak Dance Project, and then by a number of new works for the stage: AG Indexical, RoS Indexical, Spiraling Down, and Assisted Living: Good Sports II. This retrospective, which privileges dance, comes after Yvonne Rainer: radical juxtapositions 1961-2002 exhibition, which opened at the Rosenwald-Wolf Gallery (Philadelphia) in 2004.

What distinguishes the Dia retrospective is the revival of works that have been overshadowed by her iconic Trio A (1966), which was filmed in 1978 and actively preserved (as discussed by dancer Pat Catterson in her essay “I Promised Myself I Would Never Let It Leave My Body’s Memory” in Dance Research Journal, 2009). The return at Dia of Rainer’s first dance work, Three Satie Spoons (1961) as well as her Three Seascapes (1962) and Chair/Pillow (1969) not only adds to our experience of Rainer’s art and to our understanding of its historical impact, but bring it all before our eyes in the present. What makes this re-performance uniquely successful is the fact that most of the cast has been working with Rainer over the past ten years or more. Hence there is not the sense of removal from the original inspiration. The program was also effectively assembled with only short pauses and a flexible cast of five to assure both variety in the performance of Rainer’s solos for herself and an ingenious framing of the variations on Trio A.

Three separate dancers – Emily Coates, Pat Catterson, and Patricia Hofbauer —performed Rainer’s solos for Three Satie Spoons to Satie’s Gymnopédies. The lyricism of the music was contrasted with the deliberate holding of the physical motifs and the pedestrian manner in which the dancer moved in and out of them. Given the famous aversion of the performer’s gaze from the audience that characterizes Trio A, it is interesting that in Three Satie Spoons the gaze of the dancer does frequently meet that of the audience. Coates, as Rainer’s original notes indicate, stretches her mouth with her index fingers, performs a long flexed-foot attitude, a long arabesque, places her hands squarely on her hips, and draws one foot up to her pelvis in a difficult balance. (These notes can be found in Rainer’s first book, Work 1961-73). Catterson’s solo contains some port-de-bras that suggest a ballet aesthetic (she was studying ballet with Mia Slavenska when she made this piece), but done from a squatting position, and other very sculptural placings of the arms and hands about the face as well as an energetic leg extension and pivots hovering close to the floor. Catterson’s attitude is more internal and contemplative than Coates who almost seems confrontational, yet is still molded by modern and balletic dance poses that she also mocks. The third solo by Hofbauer has the dancer giving space to the vocal (squeaks), one line of text – “The grass is greener when the sun is yellow” – and, finally one long sustained “ah-oow ah-ooo” that manages amazingly to harmonize with the music. Most interesting here is that Rainer posed herself distinct technical challenges as a dancer that are implicit in yet different from the terms of the material she is also backing off from. She was rebelling against the perceived excesses of both ballet and modern dance. There is a sense that Rainer wished to trap movement in the materiality of time, which endeavor demands a great deal of technical control. There is nothing ‘light’ about Three Satie Spoons either in its intentions or its execution. There is humor, irony, poetry, and iconoclasm (of a slightly tamer nature than we find with the uncompromising minimalism of Trio A). The rebellion is there though in a less doctrinaire form.

Hofbauer performed the solos of Three Seascapes. In the first section to Sergei Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto #2 she runs in a blue raincoat making square patterns with sharp angles. Hands in pockets, she descends to the floor and lies on her side. The hands in pockets expose or show the effort it takes to go down and up without hands; she repeats the exercise over and over from different angles and in different spaces on the stage. The mechanics/technique are not hidden. In the second solo to a grinding sound score from La Monte Young’s Poem for Chairs, Tables, Benches, etc. Hofbauer snakes across the stage on one leg with the other leg limply in the air with dangling arms and antsy facial expressions that never settle into a coherent expression. This collusion with the audience about the dancer as subject who remains distant from the theatricality of subjectivity and its conventional codes, adds another dimension that is both satirical and political. While she had remained alienated from the florid emotional cues of the Rachmaninoff score by refusing to assume an expressive relation to the music in the first solo, cacophonous sound provides the background for the second solo. The third solo begins in silence when Hofbauer drops a pile of white tulle on the floor – the ultimate classical ballet signifier –and places her raincoat on top of it. She then proceeds to collapse into the tulle while emitting breathtaking shrieks. I believe she does this three times. The screams are powerful, the tulle potentially engulfing, and the sense of panic intense. These falls are all the more shocking in their explosive affect as they are done as a repeatable task.

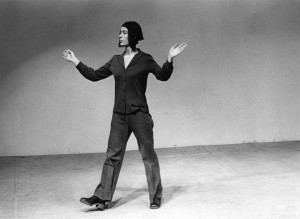

The different variations on Trio A that followed were all the more fascinating in the light of these earlier solos. This, of course, was the solo in which no phrasing was to be evident, in which no movement was repeated, in which a series of denials were enacted regarding the performer in relation to the audience, and which was performed for a little over four minutes in total silence. Keith Sabado performed it first (the first time I had seen it performed in its entirety by a male dancer); Pat Catterson then performed it in reverse or retrograde; Emily Coates then performed it ‘forward’ with Keith Sabado following her, attempting to keep looking at her in the eye as she continued through the movement; and, finally, it was performed simultaneously but non-synchronously as Trio A Pressured by all four performers to the Chamber Brothers’ In the Midnight Hour. The variations have all been done before in recent performances, but to see them one after the other also added striking new dimensions to this iconic piece. In Facing I noticed that when the Sabado follows Coates around, the effect was to accentuate the solo’s changes of levels (when her gaze is to the floor he had to be lying on the floor to meet it). Moreover, his movements about her introduced a trace movement that, while even more pedestrian than her approach, because it was unconstrained by choreography at the primary level, began to introduce rhythmic and energetic dynamics around and about the soloist’s neutral performance (Rainer has theorized this as “neutral doing”). With the Midnight Hour quartet, it seemed that certain twitchy movements were highlighted by the beat of the music and put their neutralized aspect into question. In both cases, that which the choreography denies in its famed minimalism was rendered vivid by its contrary. This also begins to suggest a certain unconscious of the choreography.

The final excerpt, Chair/Pillow for the entire ensemble was explicitly rhythmic unison dancing with chairs and pillows as objects. This piece opened out the formalist experiments of the sixties into a more theatrical arena. It served to confirm the point already made, which was that Rainer’s exploration of the materiality of movement that one might want to call choreographic minimalism was many sided and continues to resonate. Another work of the sixties, We Shall Run (1963) is announced for the May 12th program.