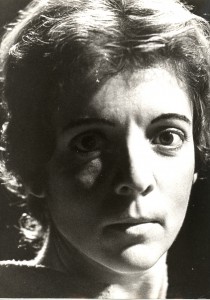

Donya Feuer, dancer, choreographer, director, filmmaker and teacher, died in Stockholm on November 6th, 2011. Her innovative approach to movement across several media and her poetic control of detail in performance had a powerful effect on theatre and dance in Stockholm for over forty years. A highly collaborative artist, her ideas and methods were influential on those with whom she worked: Paul Sanasardo, Pina Bausch, Ingmar Bergman, Ted Hughes, Mats Ek, and many other choreographers, dancers and actors. Her long career began with dance in the United States, but expanded into theatre, opera and film in Sweden.

Donya Feuer was born in Philadelphia on October 31, 1934. Her mother, Pauline Feuer, was a noted social worker and activist. She received her early dance training from Nadia Chilkovski, the well-known left wing modern dancer and dance educator. Feuer was a scholarship student at the Juilliard School of Music in New York City and then became an apprentice in the Martha Graham Dance Company; she danced with Graham on tour to Asia in 1955. Her choreographic career began upon leaving Graham in 1955 to found Studio for Dance with Paul Sanasardo in New York City. Her first important dance work was Dust for Sparrows (1958). Her partnership with Sanasardo included making and performing works for a remarkably talented group of young children; they also worked with dancers such as Diane Germaine, Manuel Alum, and Pina Bausch to produce a series of striking and original ballets: In View of God (1959), Laughter After All (1960), Pictures in Our House (1961), and the multiple evening Excursion for Miracles (1961).

Feuer went to Stockholm in 1963 initially to teach dance; she trained Mats Ek and Niklas Ek both of whom premiered in her work. She soon was choreographing productions directed by Alf Sjöberg and Frank Sundström. Her work with Sundström in 1965 on Peter Weiss’s Marat/Sade was hailed as groundbreaking. She was officially invited to join the Kungliga Dramatiska Theatern (Royal Dramatic Theatre) in 1966 as a choreographer and in 1967 she was appointed director. From then on she became closely associated with the theater work of Ingmar Bergman who facilitated the creation of her Dans Kompaniet (Dance Company). Bergman encouraged her to stage dance evenings at the Dramaten, which she did working with composer Ulf Björlin and set designer Lennart Mörk; Bergman first worked with Feuer himself when he directed Lars Forsell’s Show (1971).

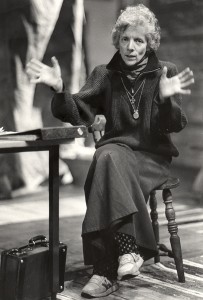

Feuer became indispensable to Bergman’s work for the theatre upon his return from Germany to Sweden in 1984. She made important choreographic contributions to his productions of Shakespeare’s Kung Lear (1984), Mishima’s Markisinnnan de Sade (1989), and Schiller’s Maria Stuarda (2000). Much of Bergman’s late theater work relied upon Feuer’s ability to make movement that determined the production’s physical language and expressive range without drawing attention to itself as dance. She brought some of these productions to the Brooklyn Academy of Music in New York. In 1996 Bergman created the role of Talata for her in his production of the opera Bakanterna.

But Feuer also directed groundbreaking productions of her own at the Dramaten, including Shakespeare’s Stormen (1968), Lars Noren’s Fursteslickaren (1973), Kristina Lugn’s Det vackra blir liksom över (1989), and Pejlingar (1978), a solo for Karen Kavli made up of a montage of Shakespearian roles. It was out of this production that she got the idea for “a play that Shakespeare never wrote”, and inspired Ted Hughes to write, Shakespeare and the Goddess of Complete Being, which was originally drafted in 150 letters he sent to Feuer over several months. In consultation with Hughes, Feuer went on to create a series of productions based on an experimental approach to Shakespearian text without plot between 1991 and 1995 with Will’s Company. This project, known as “In the Company of Shakespeare”, led to a teacher-training program implemented in secondary schools throughout Scandinavia. In 1998 she received the Stads Heders Prize in recognition of this work with children on Shakespeare and performance.

In addition to this, Feuer introduced modern dance to Sweden in the mid 1960s, and staged a series of influential dance productions that included the psychedelic pop ballet Love Love Love for the Culberg Ballet, Spel för museet (at the Historiska Museet, 1965), Ett spel om formal och mäniskor (for Swedish television, 1967), Varg rop (1971), Gud lever och har hälsan (1971), and ej blot til lyst (1985). She collaborated with Per Jönsson on Three Dances (1991) in which she danced. And she created a series of dance films beginning with the experimental De fördörnda Kvinnornas Dans (Monteverdi’s The Ungrateful Women) filmed at Faro with Bergman in 1973. This was followed by two films about Nijinsky for which she enlisted the participation of Romola Nijinsky, and created longer films on the dancer’s passion, notably Dansaren (The Dancer), which premiered at the Berlin Film Festival in 1994 and was nominated for an Academy Award. Feuer also created a number of experimental dance films in the 1970s for Norwegian television. Her work in dance was recognized by the Carina Ari Gold Medal in 1996.

She is survived by her son, Magnus Love Feuer of Los Angeles, California.

I’m still learning from you, but I’m trying to reach my goals. I certainly liked reading everything that is written on your website.Keep the information coming. I enjoyed it!

Sense of humour in an obituary? You must be kidding!