One of the most central issues in writing anything is voice, at least for me. When beginning a piece, I always ask myself, who do I want to do the talking in this poem or story? Is it a man or a woman? How old? What are his or her major concerns? Quick to anger or patient? Socially aware or a dunce? Educated or not? Humble or fat-headed? Any accent or speech impediment? If I’m writing in the third person, I ask myself whether the all-knowing narrator is a character in the story, and whether he/she/they/it can spy into the hearts of just one character or many characters?

Consequently, unlike many contemporary authors, you cannot approach my work thinking that the “I” speaking represents me. My “I’s included famous composers, images in paintings, people with Parkinson’s disease, adulterers, suburban dads, and characters from fiction, among many others. I have also used collective voices, such as the collective voice of hunters, survivors of war and pestilence, and losers of athletic competitions. I have even written material from the point of view of animals and plants.

When appropriate, I have always enjoyed creating pieces in which there is more than one voice talking. The first time I attempted a piece of creative writing with multiple voices was “The Death Song of Lenny Ross.” Lenny Ross was a minor figure of mid-20th century American history: He was a child prodigy who won $100,000 on one 1950’s television game show, and $64,000 on another. He grew up to be a key political advisor to Jerry Brown and a college lecturer. But as he aged, Lenny began acting more and more strangely. In old school parlance, he went crazy. He increasingly had obstreperous outbursts, lost his attention span, couldn’t keep a job, and eventually committed suicide at the age of 39 in 1985.

My poem tells the life of Lenny Ross in seven voices, including Lenny’s. It seems like it was yesterday, but the Pittsburgh Quarterly originally published “The Death Song of Lenny Ross” about 30 years ago! One can also find the poem in my first collection of poetry, Music from Words.

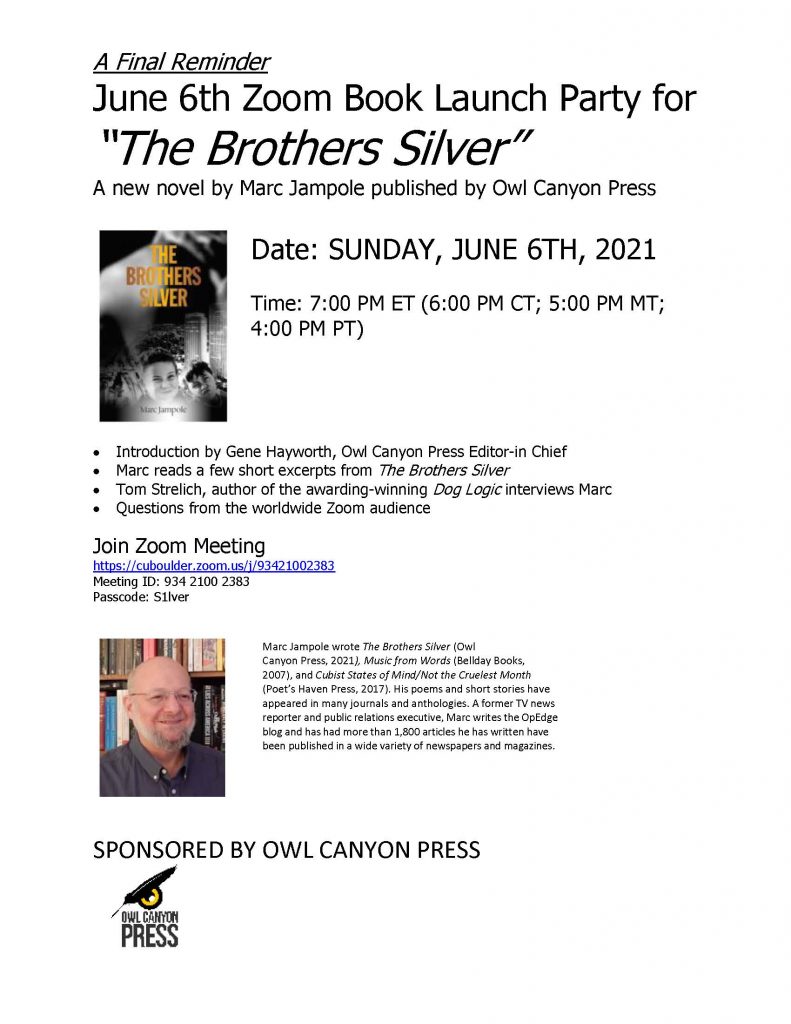

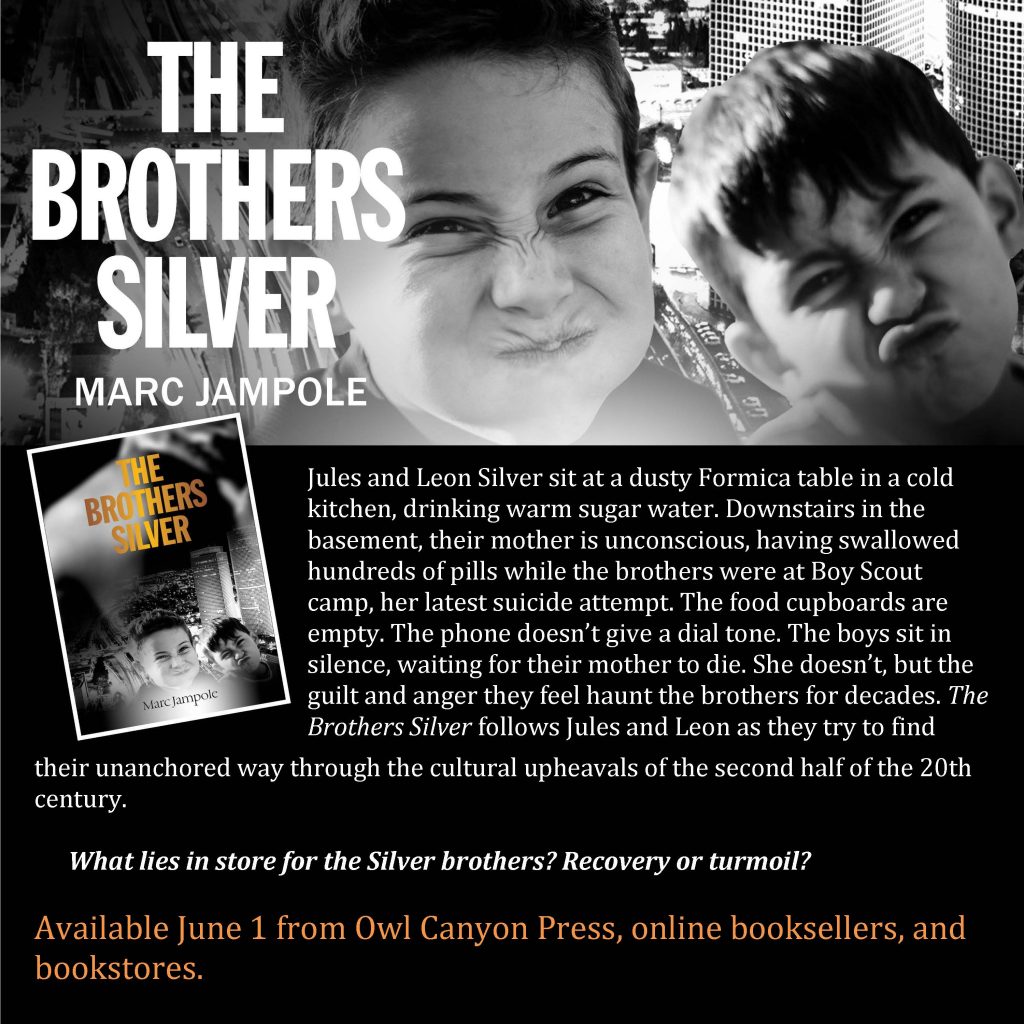

BTW (or FYI), my novel, The Brothers Silver, which Owl Canyon Press is releasing on June 1, also unfolds in what one early reader calls a “symphony of voices.” In total, the 12 chapters have 10 distinct voices, each with its own vocabulary and personality flaws. No one tells the whole story, because no one knows the whole story.

THE DEATH SONG OF LENNY ROSS

- Lenny Ross was a Whiz Kid quiz show contestant as a child in the 50’s who later became an advisor to Jerry Brown and held several academic positions.

Dow’s theory analyzes market action.

Fundamentals deal in corporate prospects.

When stocks are good, T-bills suffer,

and when the market shakes its head and shoulders

it’s getting ready to reverse direction.

What a boy you are, Lenny Ross, Lenny Ross!

What a genius boy you are!

And why not you, Lenny?

Why not you to win the hundred thousand

answering quiz-show questions

on stocks and bonds and whatever?

Why not you the youngest?

At five you talked like Walter Lippmann.

At six you built a TV by yourself!

What a boy you are, Lenny!

What a genius boy you are!

Our tort system, from English common law,

changes many features of that older land.

The principle’s the same,

that assets yield to no man save one who has them.

Eschewing class, we’re guided by associations,

men maintaining liberty by joining others openly.

as Tocqueville described, recalling Edmund Burke.

He grasped all aspects of the reading,

wrestling levels none of us had thought about,

as we sat silent, listening to his playfulness

with concepts none of us had heard before.

And yet so kind he was to all of us, his elders,

so patient telling us his thoughts.

What a mind he had, Lenny Ross,

and what a knowledge of the law.

A head that talks, an academic side man,

I know that’s what they think of me.

Great idea, Lenny! What a brain!

I want to be a man of action, commanding heads of state

I want to run for President one day.

I have a master plan.

It’s all up here!

Slow down, Lenny Ross, finish one thing!

I told him that a thousand times, at least,

then watched him stagger back and forth

among his shriveled plants and dusty chairs,

popping frozen peas at open mouth

and throwing out ideas like cannon shot.

And it was up to me to understand

that he had skipped ahead to chapter five.

Slow down, Lenny! I can’t keep up.

But he persisted with a logic of his own.

Here’s the plan:

We’ll write a treatise on the rights of students

and with the money earned, we’ll buy these artists:

Fieldes, Moore and Greaves;

minor works by minor painters.

By lending them to small museums,

their values will inflate,

and then we sell and start a franchise.

I knew his reputation: Fired from Harvard,

bewildered students, uncompleted books.

But those first flowing days in Sacramento,

those synergistic days!

We watched him use a roll of tape and scissors

to cut and splice my program.

The spaceship earth, the new age economics,

the art of Zen applied to government….

It was all there.

If things had turned out differently, Lenny Ross,

you would have been my Commerce Secretary.

A six-month freeze on wages

without a freeze on prices,

followed by a year of frozen subsidies,

after which we send a thousand troops to Spain

as warning to the Sheiks to drop the price of oil.

I’ll send the President a memorandum

when I’ve wrapped my piece on Masons.

It’s full of great ideas.

Don’t call me anymore, Lenny Ross,

I’ve had about enough of you

and your constant chatter leading nowhere.

You can’t keep quiet long enough to love me.

You touch my thigh, then start to babble economics,

then write a sentence down, then phone a friend,

remember I’m in bed and ask me

what I think of Bergman’s latest flick.

I can’t take it anymore, Lenny Ross!

Genius, shit! Just get it up and keep it up for once!

A thermo coupler made of fiberglass

Kabuki language representing social graces

Venture funds investing in technology

In five years’ time, the baby boomers will

Stendhal’s real name was

Juan Gris merely described what he

Sawmills replacing windmills along the Flemish…

You’re back home, Lenny Ross,

and we’ll take care of you.

No more taking jobs and quitting three months later.

No more lying under cars reciting lectures.

You’ll rest awhile, Lenny, and then you’ll see.

You’ll land a cushy job.

…theory of addled value William Cullen

Randolph the red-nosed option underlying

Tinto Ramm Dass vodanya Montana the Puritan

migraine persecution of the Cotton Mather

tell Jerry my name is Gemini

Carter Wilson Picket the symbol of an angry

zero coupon to beat the plowshares into Isaiah Berlin…

My voice now, Lenny,

my voice calm, first time in years,

looking through the waters of the Capri Motel pool,

hearing waves applaud with plastic hands,

smelling chlorine smoke, tasting acrid starlight fruit.

Jump, Lenny Ross.

Remove this yoke of expectation.

Jump, Lenny,

jump to freedom…

Marc Jampole

Originally published in Music from Words (Bellday Books, 2007) and Pittsburgh Quarterly Volume I, #1 (Winter 1991)